A lot of crazy stuff is happening out there right now. While I contemplated this post, a critical voice erupted in my head that sounded something like, "Are you really going to write about your dead cat when the world has so much unaddressed injustice and violence?" Thankfully I snapped to my senses. That is precisely what I am going to do because, at the end of the day, what matters most in this life is making and sustaining connections to this living and dying world. Chopper (aka Choppy and Chopperpants) taught me how to do that and so much more. So this post is a tribute to him--one of my greatest teachers--with photos to boot.

Acceptance

Chopper came to me with no whiskers in the summer of 2004. He and his litter mates had been abandoned by a stream soon after birth and most of his siblings drowned. His living sister chewed off his whiskers during this time so he only had short stubbles on his face when I adopted him from a local rescue organization. Unsurprisingly, this early trauma made Chopper pretty needy. I rarely could sit down without him wanting to be on my lap. Initially I would get frustrated by his insatiable desire for affection and frequent talking, which I interpreted as, "I'm here! Love me!! I'm here!!! Love me!!!!" I found it difficult to accomplish things, like typing papers for graduate school, with him standing on the keyboard.

Over time, however, I came to see him and myself more clearly. When I stopped doing and gave him my full attention, he did not need so much. With a little maneuvering, he could get the touch he craved, and I could still complete the tasks at hand. Perhaps more importantly, he helped me to pause more and observe myself. Frequently, I was caught up in worried thoughts. His furry self (my partner said he was the softest cat in the world) brought me back to the present moment. He reminded me to rest and receive the comfort of his noisy, unremitting purr. When I stopped trying to be somewhere else with someone else, grace came in the form of Chopper, as well as acceptance of and gratitude for what I have in this life, right now.

The Ability to Receive Love

With my former, incessant craving to be and do better, I focused much of my attention on the external world. I should be working harder, loving better, giving more, all to get some desperately sought-after approval and recognition from others. Chopper was not having any of this self-defeating performance. I could be in the foulest mood, and he still gave me the look in the above photo. I often half-joked with my partner that he could never gaze at me the way Chopper did. Try as I might to push him away, like I did with everyone else who got close to me, he just kept coming back with those big green eyes and pawed at my face until I rubbed his chin. He wouldn't even bite my hand unless it was disguised by a blanket. That fierce and gentle love again instigated a pause. Maybe I could lower the fortress I had built to protect myself from rejection and heartache and at least let Chopperpants in. He wouldn't hurt me. And he didn't. With his patient determination (and, admittedly, significant therapy), I learned I was worthy of love and that vulnerability opens the door to intimacy, understanding, and so many other good things.

The Capacity to Stay

Almost three years ago, I found a lump near Chopper's jaw. A biopsy revealed he had Hodgkin's-like lymphoma. The third time a tumor appeared, my vet said he should go to an oncologist. The oncologist tried one kind of chemotherapy. When that stopped working after a couple of months, he tried another, more aggressive (and expensive!) form that required 16 treatments. Chopper hated the car rides across town to the clinic, but he was his perky, kind self once there. Apparently he was the only cat who didn't hiss at and try to bite the veterinary staff during the blood draws.

He lost his whiskers for the second time in his life. When I grabbed my car keys, he would hide. But he endured the treatment to its completion, and we all hoped he would have at least a year of remission. No such luck. Three months later, I was back in the oncologist's office after finding another tumor. The doc said he didn't want to give up yet. We tried a third kind of chemotherapy that I could give him at home. I arranged for him to get the necessary blood work done at a nearby veterinary office, as he began to howl and throw up when we arrived at the oncologist's office. Propelling such anxiety for short spells of remission stopped making sense.

When another tumor reappeared this past May, I called off the chemo and weaned him off the steroids he had been taking. He stopped being afraid of my car keys and resumed being his playful, cheerful, talkative self. He would serenely sit on my lap while the lovely Carrie Donahue put acupuncture needles in his back, and he did not balk at me shoving supplements down his throat twice a day.

Then he began having trouble breathing. We started the steroids again. Another tumor appeared and quickly enveloped his throat and chest. The tumor eventually became infected and made his breathing extremely labored. On January 7, 2015, Carrie came over to our house and euthanized my beloved cat who was, at that point, gasping for air. He died peacefully in my arms, and I am forever grateful to Carrie and thankful I had the resources to let him go in this way, before he could no longer breathe.

Why am I recounting the details of this sad tale? Because I had no idea I could witness such suffering without fleeing the scene (which is my favorite definition of compassion) until I experienced Chopper's prolonged struggle with cancer. I frequently wanted to bury my head in the sand and avoid the painful parts of his illness, but I didn't. I sat with him. I loved the shit out of him. I let him go. I never want to go through this process again with a pet or human being, but now I know that I can. And that makes all the difference. May you rest in peace, sweet Chopper.

to live in this world

you must be able to do three things to love what is mortal; to hold it

against your bones knowing your own life depends on it; and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go

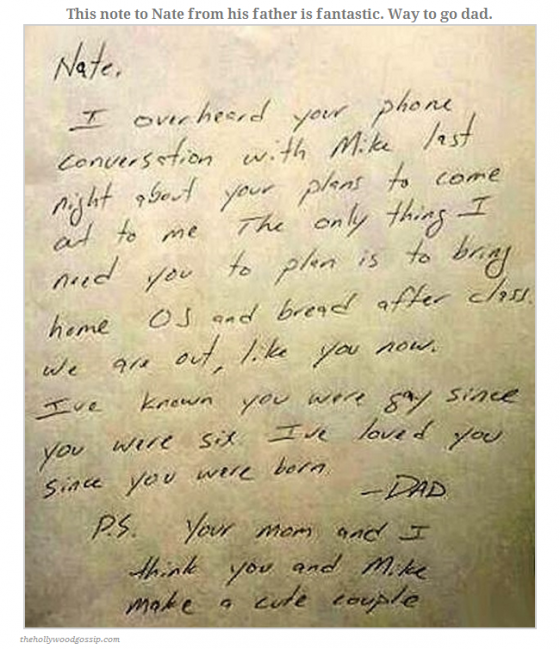

U.S. District Judge Barbara Crabb's recent ruling of Wisconsin's constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage as unconstitutional has inspired me to write about the direction in which I would like to see my own field of "marriage and family therapy" go.

U.S. District Judge Barbara Crabb's recent ruling of Wisconsin's constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage as unconstitutional has inspired me to write about the direction in which I would like to see my own field of "marriage and family therapy" go.

room for our wedding night. The room was located at the top of a winding set of stairs. I surrendered my hope of arriving there. "Let's just go home," I sighed to my partner. We were going to do no such thing he informed me gently. He gingerly hoisted me over his shoulder and carried my whimpering self to our sought-after destination. This feminist never imagined being carried across a threshold on my wedding night. Alas, the universe had other plans for me.

room for our wedding night. The room was located at the top of a winding set of stairs. I surrendered my hope of arriving there. "Let's just go home," I sighed to my partner. We were going to do no such thing he informed me gently. He gingerly hoisted me over his shoulder and carried my whimpering self to our sought-after destination. This feminist never imagined being carried across a threshold on my wedding night. Alas, the universe had other plans for me. Turning loving attention toward my experience remains an ever challenging practice. This particular episode continues to represent what one of my mentors calls (and don't read on if swearing offends you) "another fucking growth opportunity." But I am growing. I keep thinking about the many moments during my wedding day when I felt connection, beautifully defined by

Turning loving attention toward my experience remains an ever challenging practice. This particular episode continues to represent what one of my mentors calls (and don't read on if swearing offends you) "another fucking growth opportunity." But I am growing. I keep thinking about the many moments during my wedding day when I felt connection, beautifully defined by