In my line of work, particularly with couples, the old adage, "Would you rather be right, or happy?" comes to mind a lot. When large differences exist, as is frequently the case between partnered individuals, digging in our heels and claiming rightness (or the other person's idiocy) becomes oh-so-easy when we feel like our perspectives or even our selfhood are being threatened. That to me is the key: we jump into right/wrong, good/bad stances when we feel afraid. Fear is a natural emotion that arises when we feel unsafe. To fight, flee, or freeze makes perfect sense if our lives are really on the line, such as in instances of violence, abuse, and neglect. However, individuals in intimate relationships frequently resort to this "reptilian brain" reaction when our experience of threat feels real but is not actually true.

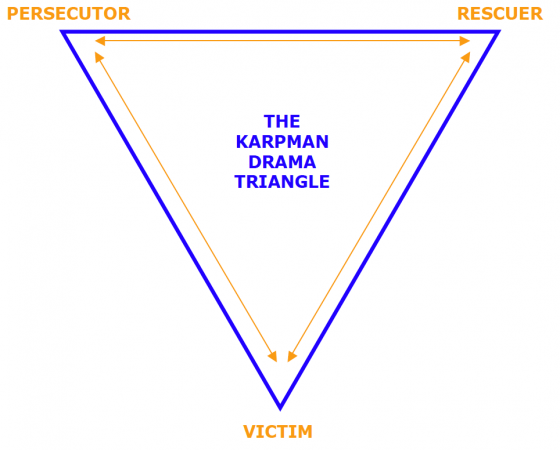

The classic pursuer-distance dynamic captures such emotional reactivity. One person starts to see danger signs flashing in the midst of conflict and so begins to retreat (i.e. flee) from the scene. The other person becomes emotionally flooded with a fear of abandonment and chases after the other, raising her voice and refusing to let the interaction come to a halt (i.e. fighting). The fleeing partner, now feeling like a hunted animal trapped in a corner, threatens to leave the house or the relationship and/or explodes in rage. When all is said and done, both people feel ashamed, spent, and remorseful. Sound familiar?

Psychiatrist Dan Siegel helps us to understand the evolutionary history of our emotional reactivity via his brain hand model. He also offers an alternative to going reptilian: pausing long enough to identify the fear and not immediately react to it. When we can calm our nervous systems enough to recognize we are actually safe, such as through deep breathing exercises, we can reengage the more recently developed part of our brain that has the capacity to empathize, cooperate, problem-solve, and be creative.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vESKrzvgA40

In contrast, when we react to fear by making others or ourselves bad or wrong, we're using aversive judgment, or what Tara Brach calls "an aggressive force that separates." The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines aversive as "tending to avoid or causing avoidance of a noxious or punishing stimulus." When we use aversive judgment, we make others and ourselves (when the judgment is directed inwards) noxious and punishing entities. In other words, we reinforce a perception of the world as an inherently dangerous place where enemies lurk around every corner. In such a world, war and the establishment of hierarchies composed of "better" and "worse" people become the answer to conflict.

Tara Brach reminds us that this us/them, superior/inferior mentality is also an evolutionary artifact. When we lived in small groups, the framing of outsiders as threats to our survival could and did strengthen internal group cohesion. With our twenty-first century brains, however, we have the evolutionary potential to recognize our interconnectedness and feel compassion for the suffering of others and ourselves. We therefore can practice working with, not against, our fears and so choose not to violate others' or our own dignity when we feel endangered. We can remain whole.

Not reacting to our fears does not mean we tolerate harm to others and ourselves. This is where wise discrimination comes in. We can acknowledge that those who cause suffering are themselves suffering and decide the best course of action is to direct our attention elsewhere or leave the relationship. Standing up for ourselves and acknowledging another's struggles are not mutually exclusive phenomena. Nevertheless, how we take stands matters a lot if we are committed to stopping the war. If we decide to make another bad or wrong for their actions, we're back in the land of aversive judgment. A nonviolent approach, in contrast, asks us to investigate our own unmet needs in the relationship and communicate our desire to honor our own value rather than violate it for the sake of staying in relationship with someone who mistreats us.

At the end of the day, being right versus happy does not quite capture the stakes of social interactions. I would rather deepen my understanding of the human condition so as to be able to recognize quickly that when we harden, whether by becoming self-righteous or emotionally disengaged, we are trying to protect ourselves. Until we can detect and make visible the soft underbelly beneath the daggers and shields, we will not forge authentic connections and a sense of belonging, both of which, in my experience anyway, are the sources of our greatest contentment. To borrow from Brene Brown, “Vulnerability is the birthplace of love, belonging, joy, courage, empathy, and creativity. It is the source of hope, empathy, accountability, and authenticity. If we want greater clarity in our purpose or deeper and more meaningful spiritual lives, vulnerability is the path.”

* This post draws heavily from Tara Brach's wonderful talk "Part I: Evolving Toward Unconditional Love."