My, oh my, am I hearing a lot of blaming these days! A Time article title sums up the current U.S. blame game: "In New Poll, Americans Blame Everyone for Government Shutdown." Although I have already written about the Karpman triangle (also called the drama triangle) elsewhere, I know I am yearning for a reminder of what life can look like when people are "proactive rather than reactive, self responsible rather than blaming."* The triangle serves to clarify how we get stuck in vicious blaming and shaming cycles within our private and public relationships. Using the triangle, we can unmask an issue and respond to it in more skillful ways. So back to the triangle I go!

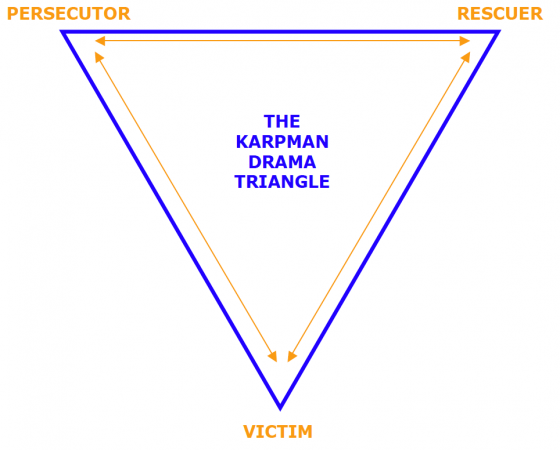

Psychiatrist Steven Karpman introduced the triangle in the 1970s. Essentially, the triangle's three points represent the following roles that adults play when engaged in relational power struggles: persecutor, rescuer, and victim. The persecutor seeks to control others via anger, criticism, and blaming, without recognizing the fear driving this abusive behavior. The rescuer tries to control the situation by being helpful, nice, and strong, not seeing that when we try to rescue others from their problems, we prevent them from drawing on their own strengths and resources to resolve issues (i.e. we treat others as victims). The victim also seeks to control others by assuming a position of overwhelm or paralysis in the face of managing his or her life. As victims, we want others to rescue us or whip us into shape.

Importantly, these roles portray a sliver of who we actually are, even if we have grown comfortable in one of them over time and, thus, seemingly inhabited it forever and always. These roles are also dynamic. In other words, we may assume the role of victim in one situation and persecutor in another or morph into a new role when our feelings change about the situation. For example, the rescuer may get tired of saving the day and explode at the victim, thereby shifting to the persecutor role for at least a little while.

The primary problem with hopping on the triangle is that we give up our power. We forget about our capacity to utter the following words,

I'm responsible for what I think, do, say. If something bothers me, it is my problem. If you can do something to help me with my problem, I need to tell you, because you can't read my mind. If you decide not to help me, I'll need to decide what I'm going to do next to fix my problem. Similarly, if something bothers you, it is your problem. If there is something I can do to help you with your problem, you need to tell me. And if I decide not to help you with your problem, you can work it out. You may not handle it the way I might, but you can do it. I don't need to take over.

In current U.S. society, I perceive a lot of persecutory public speech, whether on Facebook walls or CNN. I also sense a lot of self-rescuing via various disengagement strategies, such as drinking alcohol, smoking marijuana, taking prescription pills, over-eating, and watching TV or playing video games for hours on end. These strategies often come to the fore when we are feeling overwhelmed and just want Calgon to take us away (aka assuming the victim stance).

Staying present, engaged, and self-responsible is hard. Really hard. But the benefits of manifesting this aspiration overwhelmingly outweigh the costs to others, ourselves, and our planet. Those benefits include a sense of connection and belonging--of feeling seen, heard, and valued and that we are part of something larger than us.** Such a sense of connection and belonging ultimately removes the thrill of persecuting, rescuing, and staying in the one-down position. In Robert Taibbi's terms, when we step off the triangle, we "can be responsible and strong, and yet honest and vulnerable. [We] can take risks, are not locked in roles, and, hence, can be more open and intimate."

Leave it to a 16-year-old young woman to show us what leaving the triangle behind can look, sound, and feel like. As Malala Yousafzai said in response to Jon Stewart's question, "When did you realize the Taliban had made you a target?"

I used to think that the Talib would come, and he would just kill me. But then I said, 'If he comes, what would you do Malala?' Then I would reply to myself, 'Malala, just take a shoe and hit him.' But then I said, 'If you hit a Talib with your shoe, then there would be no difference between you and the Talib. You must not treat that much with cruelty and that much harshly. You must fight others but through peace and through dialogue and through education.' Then I said I will tell him how important education is and that 'I even want education for your children as well.' And I will tell him, 'That's what I want to tell you, now do what you want.'

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjGL6YY6oMs&feature=kp

* This quote and the next comes from Robert Taibbi's Doing Couple Therapy. I also drew heavily on Taibbi's book in the following portrayal of the Karpman triangle.

** See Brene Brown's Daring Greatly for more on the human need for love, connection, and belonging.