An honorable human relationship--that is, one in which two people have the right to use the word "love"--is a process, delicate, violent, often terrifying to both persons involved, a process of refining the truths they can tell each other.

It is important to do this because it breaks down human self-delusion and isolation.

It is important to do this because in doing so we do justice to our own complexity.

It is important to do this because we can count on so few people to go that hard way with us.

My partner and I frequently joke about my compulsion to tell the truth. I therefore was not surprised to find myself growing increasingly twitchy while reading the epilogue of Janis Spring's After the Affair, a book I have been using with couples who are attempting to recover from infidelity. In it, she wrote, "Keep in mind even if you're determined to rebuild your relationship, there's no correct response: It's not always better to confess or to conceal. You may decide to tell in order to get close again, and you may decide not to tell in order to get close again."

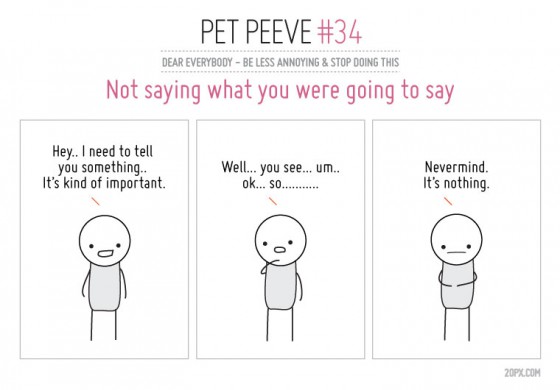

Now I try very hard not to go all black and white on the world. However, while reading this chapter I found my internal voice screaming, "You cannot hide an affair! You have to tell the truth to your partner!!" My intense reaction to this epilogue has gotten me quite reflective about interpersonal honesty and particularly its uses and misuses.

Having learned the wisdom of going inward when I want to rant outward, I quickly realized the extent to which my direct experience with betrayal amped up the volume of the voice that wanted to argue with Spring's epilogue. It just plain sucks to have someone you trust deeply lie to your face only to later find out that they did so and chose not to tell you the truth. I do not think Rich was exaggerating when she claimed,

When we discover that someone we trusted can be trusted no longer, it forces us to reexamine the universe, to question the whole instinct and concept of trust. For a while, we are thrust back onto some bleak, jutting ledge, in a dark pierced by sheets of fire, swept by sheets of rain, in a world before kinship, or naming, or tenderness exist; we are brought close to formlessness.

That excruciating pain often worsens when the individuals doing the deceiving believe they were protecting you, for your own good. The message one often hears in this action is, "You don't think I can handle the truth." I, for one, would prefer to be treated like an adult, not a victim who needs to be rescued from my hurt feelings.

Spring wrote, "There's no way to predict with certainty how your partner will react, today or over time, but if your knowledge of your partner's character and personal history leads you to suspect that your secret will shatter his or her sense of self, it's probably wiser to keep the truth to yourself." I can live with this statement if the partner doing the concealing has strong evidence--beyond their subjective assessment--that the truth will actually crush their partner. After all, such justifications are frequently a projection of one's own fear onto another. The "my partner can't handle the truth" assertion can and frequently does serve as a flight from accountability, to our loved ones and ourselves. When someone sidesteps their own fear by accusing another of being too fragile or overly sensitive, that is an attempt to control the situation. It it crazy-making behavior, but it does not mean the accused is crazy. Or too weak to hear the truth.

I also would rather hear people acknowledge their self-serving intentions when using deception. These frequently include shielding themselves from a partner's anger, avoiding a confrontation with their partner's pain, and/or preventing the loss of the relationship. Honesty about our vulnerability in the face of difficult truths can spur empathy, compassion, and connection, even from the individuals experiencing betrayal. I thus view self-honesty as part of the "honorable human relationship" of which Rich spoke.

With all of that said, I've been paying a lot more attention to the way we deliver our truths, particularly as I grow more committed to living mindfully. The notion of wise speech in Buddhism has been especially useful in thinking about how to "refine the truths" I tell. The guidelines for wise speech "urge us to say only what is true, to speak in ways that promote harmony among people, to use a tone of voice that is pleasing, kind, and gentle, and to speak mindfully in order that our speech is useful and purposeful."

Wow is following these guidelines hard. It's so easy to exaggerate the truth, use biting words, harden our tone, and blurt out the first words that come to mind in the heat of a moment. What is more, reverting to an either/or framework when we are upset, hurt, or fearful can happen in the blink of an eye. In other words, we often need oodles of practice (and self-compassion for the numerous times we flub at executing wise speech) to hold and express conflicting emotions and thoughts in a single space--to be angry and loving; to speak honestly, gently, and kindly about difficult subjects.

To speak mindfully also means acknowledging that not all our thoughts and emotions need to be shared. As Carlin Flora wrote, "Constant venting of tiny stressors and criticisms can quickly hack away at the core of a relationship." Taking the time to discern what matters most can help us to discover when we are expressing truths that are actually helpful to our partners, ourselves, and the relationship.

Moreover, given our negativity bias as human beings, we often need to actively work on highlighting the positive aspects of our lives and relationships. I like the Gottmans' recommendation of cultivating a fondness and admiration system in our relationships, as it allows us to go from "scanning the environment for people's mistakes and then correcting them to scanning the environment for what one's partner is doing right and building a culture of appreciation, fondness, affection, and respect."

I still believe that revealing the truth of infidelity is more beneficial than hiding it in most cases. I also aspire to speak my truths wisely. In the eloquent words of Charlotte Kasl: "[T]here is no beauty in words that are intended to undermine, wound, shame, or harm...There is music in our words when they come from a kind heart and mind. A deep part of spiritual practice is to drop back inside and speak with intent to be clear, true, and kind."