Guilt. It comes up often and mercilessly for many of the clients who walk through my door. I've begun to see it as a probable symptom of over-responsibility, as many people mention it in the context of trying to set boundaries with loved ones and feeling like they have no right to do so. After naming the guilt, clients say things like,

I shouldn't complain about being there for my mom during this difficult time in her life.

My friend is in crisis. It's selfish for me to focus on my own needs when they are on the edge of a cliff.

I have to answer the phone when my brother calls. It's true he asks me for money 95% of the time that we talk, but I'm his sibling. I can't ignore him.

As I've noted before, any time I hear a "should" (aka "have to," "need to," "supposed to"), I pause and get curious about this sense of obligation. Many times, we learned from our families, religion, the media, or some other external source that there is a right and wrong way to go about living life. In other words, "shoulds" are inherently evaluative. Judgments of this sort are not themselves bad or wrong, but they tend to limit our our sense of possibility rather than grow it. In all of the statements above, I hear some implicit, rigid rules about how a person in a particular role--child, friend, parent--is supposed to behave. But who said it has to be so?

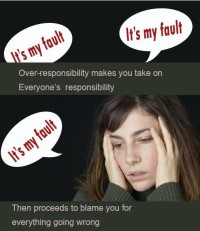

An important step for those of us who tend toward over-responsibility is to inquire into where and how we learned to view the world as a place that needs us to take over. More often than not, we have unconsciously taken on a role that helped us to survive a relationship or difficult situation at one point in time. But, as time marches on, this initially useful strategy serves to undermine our connection to others and ourselves. As Susan Burden unabashedly states in a great article called "Tracking Over-Responsibility in a Family System,"

If the over-responsible person has a hard time taking care of his own needs, it's even more difficult for him to establish an emotionally close relationship with another person...If my focus is inside his head, aware of his pain, anticipating his real or imagined needs, and I assume responsibility for them, then I am giving up self. If I deny what's inside me, I have very little to share with him. Moreover, how can I respect the person whose boundaries I'm invading? My taking care of him implies that he is incapable of taking care of himself, and that's no basis for respect...Over-responsibility is a form of dysfunctional caretaking. It's an attempt to keep one away from painful feelings, but the price paid is high. The chronically over-responsible person will find herself in relationships that are based on duty and obligation, and riddled with doubts and mistrust rather than on caring and respect.

What those of us who jump into an over-responsible role too often neglect is how we're actually undermining someone else's ability to draw on their own resources and strengths to deal with the ups and downs of life. We end up trying to be responsible for rather than to people.

I became painfully aware of my own tendency toward over-responsibility on the heels of a client's suicide. Feeling acute helplessness and powerlessness, I initially jumped into a rescuer role. Especially when I saw someone struggling, I tried to do everything in my power to "fix" their problems. With the assistance of skillful colleagues, I began to see how all this over-doing for others was made in an effort to avoid my grief and the effects of this traumatic event on my own personal and professional life. I also gained a clearer understanding of how I was not actually helping anyone when I put on this savior hat.

The connection between over-responsibility and disrespect strikes me as especially pertinent when facing the institutionalized racism that is blatantly appearing in the form of widespread police violence. If we are going to work in solidarity for justice and peace, those of us who are outsiders to the communities of color facing racialized oppression and domination day in and day out would benefit from inquiring into how we are approaching our responsibility to these communities. I have seen a lot of media about white people not stepping up and speaking out against systemic racism and violence (i.e. being under-responsible) and this is certainly an issue. But the opposite problem also persists, and has been discussed in multiple ways, including Teju Cole's powerful article about the "white-savior industrial complex." As he asserts, humility and respect for people's agency is critical to acting on a "good heart":

there is much more to doing good work than 'making a difference.' There is the principle of first do no harm. There is the idea that those who are being helped ought to be consulted over the matters that concern them...If we are going to interfere in the lives of others, a little due diligence is a minimum requirement.

In short, the guilt tied to over-responsibility not only negatively affects our day-to-day interactions with others but also has troubling, broader social and political implications. Audre Lorde gets the final word on this point:

all too often, guilt is just another name for impotence, for defensiveness destructive of communication; it becomes a device to protect ignorance and the continuation of things the way they are, the ultimate protection for changelessness.